More than 1,100 pounds of sludge was removed from the half-million-gallon tank last year, he said. “What they’re losing in the seas, we collect,” García-Ortega said. In between cleanings, it nourishes other tank-dwellers, such as oysters and plants. The waste detrimental to marine ecosystems can be cleaned out of a tank and used as fertilizer for plants. Land-based systems don’t have such a problem. In other countries, where aquaculture is much more common than the United States, it has drawn controversy because of the concentration of nitrogeonous fish waste polluting the water. The aquaculture most familiar to people involves offshore cages. The center began amplifying its efforts to research land-based systems about 5 1/2 years ago, after García-Ortega’s arrival, who had done similar marine research in Mazatlán, Mexico. “That’s kind of a different approach than most people do,” said assistant professor Armando García-Ortega. PACRC’s latest projects, which it hopes to scale up in the coming years, focus on what sounds like a misnomer: land-based aquaculture.

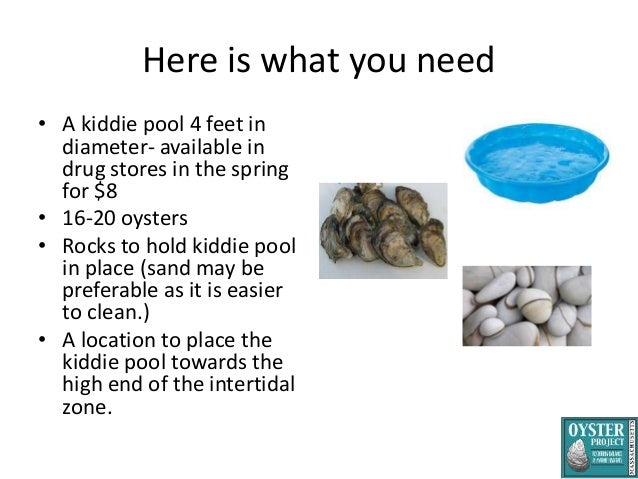

In a much larger tank - half a million gallons of water - yellowtail and grouper swam together, near a burbling downweller of growing baby oysters, called spat, and an in-water cage of non-native snapper. In another, large grouper gulped their breakfasts. In one tank, robust yellowtail (kahala) sliced the surface with their fins and gobbled up the food. They dropped the slim fish into above-ground tanks, each containing more than 33,500 gallons of seawater.

Working at the university’s Pacific Aquaculture and Coastal Resources Center site in Keaukaha, the pair donned gloves and picked up small plastic baggies of silvery sardines. HILO - On a recent Wednesday, University of Hawaii at Hilo students Anne Sophie Marques and Albane Parthenay headed out to feed the fish.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)